My name is Maxwell Jensen. I was born and raised in Norway, but my story begins in Poland. My father was a naval officer from Gdańsk who sought asylum in Norway in 1986, and my mother immigrated from Zambrów in 1996.

The goal here is to share some insights that might be relevant to Norwegians, or really, anyone who finds multicultural exchanges interesting. We all know we live in a world of global exchange – not just of goods, but of ideas and culture. With this short essay, I hope to offer some insights and constructive criticism that everyone can use to expand their worldview. While I don’t believe that simply importing people of fundamentally incompatible cultures constitutes a valid social policy, I do believe every culture offers at least one thing that can widen our perception of the world for the better. And let me be clear, this is a two-way street: my life in Norway has had a formative, profoundly positive impact on how I view the world, which I will get into later.

If we don’t open up our minds – or at least give a cursory glance – to how other people do things, we might end up like the Americans. Notice how Americans enjoy films, but generally only if they are made in Hollywood. If a film is set in a foreign place, it’s almost always through the lens of an American protagonist. Even one of their most popular films set in Shogunate Japan is about Tom Cruise as a samurai. This insularity can have amusing consequences, like when the New York Stock Exchange incorrectly hoisted the Swiss flag to announce Spotify’s listing – an error made by people who likely spent more on their education than you spent on your house. You get the idea.

Now, is that such a big issue? Actually, yes. An insular society can develop some unhealthy blind spots. For instance, a 2019 Pew Research Center study showed that many Americans believe any form of government intervention in the social sphere would undermine democracy. Both those who view “socialism” negatively and those who view it positively in the USA seem to understand the term only through brief history lessons about the Soviet Union and some headlines about Venezuela. It’s easy to see how simply exposing oneself to foreign cultures, even through films, would dispel such an ill-conceived and almost childishly simple understanding of basic concepts. A few films about Europe – not through Tom Cruise, but actual Europeans – would quickly make them understand that, no, we are not “socialist” countries in that sense. It is no wonder there is so much misery and confusion in the USA when people simply don’t know any better.

Culturally and socially, Norway is not in such a dire state, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t room for improvement, or that Norwegians don’t live in some kind of bubble. Ultimately, we all do. It’s only a matter of extent. By no means do I consider myself some learnt world traveler; I speak only three languages and have never travelled outside of Europe.

There are many reasons why I decided to move to Poland. Not all of them are related to the cultural or political situation in Norway, but they are a big factor. They are too numerous to list here, so I will focus on the most relevant.

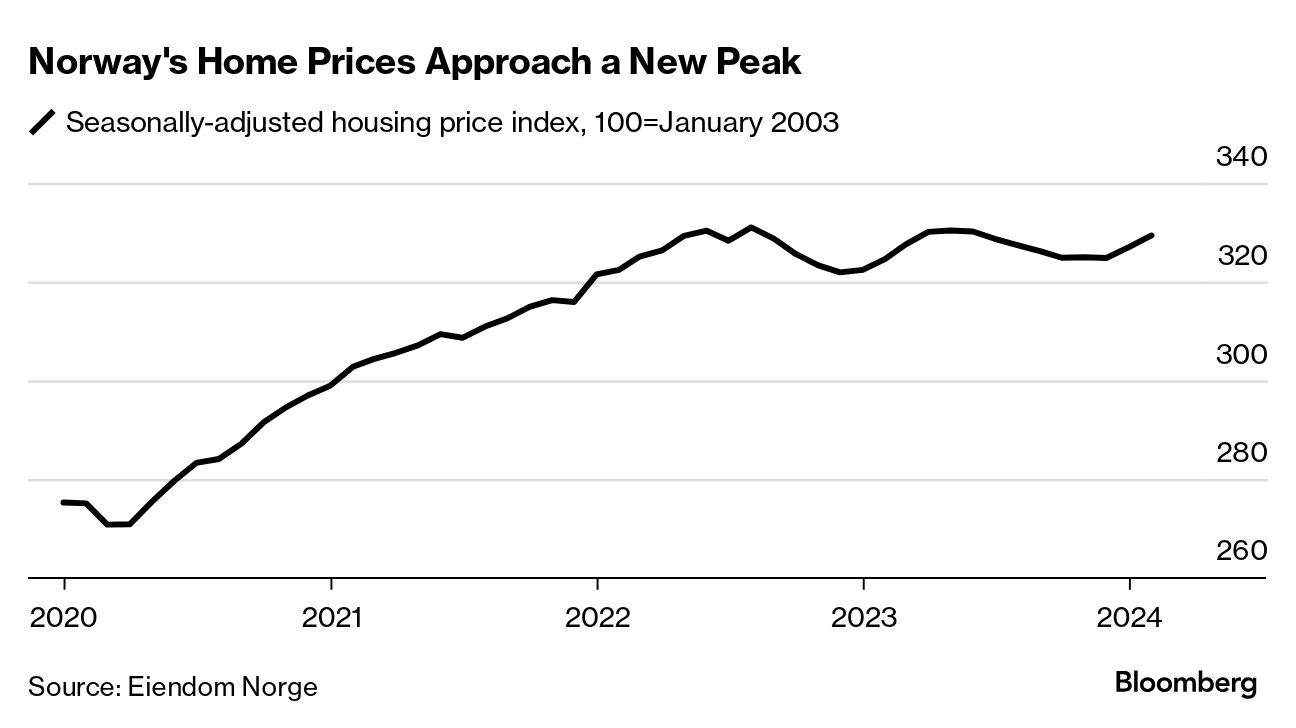

Why did I move to Poland? Let’s start with a simple, economic reason that everyone can understand: the real estate situation in Norway. For my generation, it is, to put it bluntly, absurd beyond belief. As a result of the 2008 mortgage crisis, Norway implemented extreme austerity measures that should have been lifted years ago. The biggest of these is the limitation of a mortgage to five times your annual income. This was a reasonable measure in the wake of the crisis, but after more than a decade, it has resulted in a crippled real estate market.

From Bloomberg

Because of this extremely tight mortgaging limit, companies were forced to build only the housing people could afford within that narrow margin. Five times your annual income is not a lot. Combine that with a fragile fiat currency brought to its knees by a regional conflict or a US presidential election, overall claustrophobic economic regulation discouraging foreign investment, and you have a real estate nightmare on your hands. Even if the government lifts this limit, it will take at least a decade for the market to recover as prices will shoot up for the foreseeable future.

Considering I am 29 years old, I am not waiting until I am nearing retirement before I have a chance of applying for a mortgage on a regular house. And no, my wife is not going to be forced to work for a mortgage. This led me to a startling thought: if a medieval peasant six centuries ago could afford a place to live – working as little as 120 days a year – then I should be able to afford a decent house with a regular job in the 21st century. Nobody is going to convince me this is normal. Mortgaging in the first place is an aberration, a deep perversion of modern economics. The Catholic Church1 expressly forbids usury, as it is a sin. This isn’t exclusive to Norway, of course, but here the situation is exceptionally bad for my generation. The fact that dual income is an essential prerequisite should cause far more outrage than it does.

Poland was the only country in Europe that had economic growth during the 2008 crisis. Its real estate situation is not ideal either, thanks to global inflation and other developments, but it remains sane. There are no extreme austerity measures limiting your mortgaging possibilities. You can afford a mortgage with one income. For this reason alone, I struggled to see a future in Norway.

This has wider personal ramifications. Attracting a suitable spouse becomes immediately more difficult if you do not have a house, at least in a country like Norway where two-generation households are the norm. In many other countries, like Poland and Spain, multi-generation households are common. Having your parents in the house with your kids has immense benefits. Daycares in Norway are necessary only because both parents are forced by the perverted economy to work, and there are no other adults in the house to take care of the children. This isn’t just about necessity; it’s a different social model. Why should a stranger take care of your children? Food for thought.

Of course, there is more to life than economics. I do not live by work, or how much cool stuff I can buy on AliExpress, but I thought I would start with something that – at least I think – should be the most readily digestible for the common reader. Let’s move onto more meaningful, important topics. However, I will have to compress my statements significantly, otherwise I would be writing a book, not an Internet article. Bear that in mind, in case the following statements feel superficial or incomplete.

Perhaps the easiest way to see the difference between Polish and Norwegian culture is observing the way 17th May Constitution Day in Norway is celebrated compared to the 11th November Independence Day in Poland. Constitution Day in Norway feels more like a birthday, whereas Independence Day in Poland is more like a funeral. Somebody from Norway attending an Independence Day march in Poland might be very surprised by this, until you remember that the Polish state’s sovereignty was built on blood and sacrifice. Hundreds of thousands of young men had to sacrifice themselves so that today we can be free. The Polish Constitution is written in blood of my great-grandfathers.

Meanwhile, with the way Norwegians celebrate Constitution Day, you would think the Norwegian Constitution was written by Coca-Cola. My intention is not to degrade the significance of the Norwegian Constitution, of course, but the celebrations are distinctly more upbeat than in Poland. This is very interesting, because Norwegian independence from Sweden in 1905 could have easily been very bloody. In fact, it is one of the things that sort of started driving me nuts when I learned of it, back when I was doing my hunter’s licence in 2023: Norwegians in the 19th century were armed to the teeth. This was the case in most of Europe, but especially Norway. The reason why Sweden didn’t invade is not because everyone in Scandinavia was oh-so-polite, but because the quintessential hobby of nearly all Norwegian men was sharpshooting. If Sweden were to invade Norway, it would be a protracted military nightmare where every window and treeline could hide a crack shot. Sure, Swedes on the general did not want war, but when has public opinion ever stopped pointless bloodshed? In other words, the Norwegian Constitution could have also been easily written in blood.

Photo of the Langseth shooting club from the 1950s. Taken from the digital museum of Museene i Akershus.

At the same time, I have almost never heard about this from any Norwegians I have been with. The old Norwegian gun culture is fascinating. One of the retired gunsmiths I spoke with said how just 30-40 years ago it was quite normal for young teenagers to carry hunting rifles in public. It did not cause any alarm. Nobody called the police to summon a SWAT team to the location. Why would it? There is nothing wrong with weapons, only people that may abuse them.

Even today we still have Switzerland and Czechia as some of the most heavily armed nations on the planet, which do not have any more serious problems with firearms-related criminality than Germany or Norway. Yet, despite this, in a lamentable way, Norwegians allow their culture to be infected with hysteria from media and political talking points originating in the USA. My hunting instructor told me how people regularly summon the police when they hear gunfire in the nearby forest, only for the SWAT team to find – to nobody’s surprise – a hunter who was performing normal hunting-related activities in the forest.

The point here isn’t legislation or morality surrounding guns. My point here is to highlight the symptom of a deeper cultural sickness. It’s not something exclusive to Norway, of course. Poland to some extent also suffers from this, but I will get to that.

The image of a SWAT team descending on a lone Norwegian hunter is the perfect metaphor for a society that has become afraid of its own shadow. The farmer-sharpshooter who once guaranteed the nation’s sovereignty has been replaced by a citizen who is terrified by the very tools that secured his freedom. This citizen no longer trusts his traditional roots, or even himself. Norwegians have forgotten many aspects of their great culture. As cold as it is to say, a large chunk of Norwegian society has transformed from intrepid opportunity-seizing vikings, to largely risk-averse people of the modern world who freak out over hearing a bang in the forest.

The modern Norwegian tradition of rolling up to your 2,000,000 kr hytte, in a brand new Tesla on a neat access road, with tap water and electricity does not have the same ring to it.

In Poland, a different instinct prevails. A history of being betrayed, occupied, and erased from the map has taught Poles a healthy skepticism towards entrusting their safety entirely to outside forces, including their own state. Self-reliance is not a hobby; it’s a deeply ingrained historical necessity. The idea of calling an armed response team because you heard a hunter in the woods would be met with ridicule, because the forest and the hunter are still understood as normal parts of the landscape of life. Granted that Poles still have a somewhat irrational aversion to firearms, but I digress.

This allergy to risk, this outsourcing of responsibility, doesn’t stop with guns. It seeps into everything. It’s in the way children of Norway are raised in sanitised, bubble-wrapped environments, the way social discourse demands absolute conformity to avoid offence or radical changes, and the way the state is expected to provide a safety net for every poor decision. It is the slow, comfortable march towards a society of dependents, and it was a future I could not see myself in. I still held out hope that this would change, but it didn’t. If anything, it has become far worse after I resettled.

Is Poland a super Catholic and traditional society amidst a hyper-liberal Europe? Some people would like you to believe that, but this is not true at all. Modernity has also come to Poland. With a dramatic increase in affluence – possibly exceeding that of Norway as of 2025 – Poles have also become drunk on modern convenience and ideals. Where before God and the Vatican was the binding glue of society, these days around Poles are largely religious only on Sunday Mass. Even then, it is up for debate how many attendees actually pay attention to the worship. Just the same as in other European countries, clothes that would have been unthinkable on an adult woman 20 years ago are now the norm for 13-year-old girls today.

So why do I care? What has tangibly changed in my situation, if Poland is slowly heading towards the same degree of liberalisation and ways of thinking as Norway? The answer is about trajectory and foundation. It’s one thing to be on a moving train. It’s another thing entirely to know where the train started and how fast it’s going.

Norway’s train left the station of deep-rooted tradition long before I was born. It has been moving at full speed for 50 years, fuelled by oil wealth and insulated from the shocks that force a society to remember what matters. The journey has been so smooth for so long that the destination – a society of comfortable, risk-averse dependents – is not just in sight, it’s the next stop. The cultural battle is, for the most part, over. The consensus has been set. I hope I am wrong in this.

Poland’s train just left the station. For half a century, it was stuck behind the Iron Curtain, a forced immobility that, funnily enough, preserved much of its cultural foundation. The historical memory of hardship is still fresh. The family unit is still the undisputed centre of life. Religion, even if practised with less fervour, still provides a moral bedrock that is simply absent in Scandinavia.

Memory of those from my home town, who have given their lives for the liberation of Poland. Photo by Zambrow.org

So yes, Poland is liberalising. Yes, it is wrestling with the same demons of modernity. But the crucial difference is that here, it is still a wrestle. The battle is still raging. In Poland, tradition is not a museum piece; it’s an active, powerful force in the public square. The hundreds of thousands men who perished in battle are real; they move people, even if jaded by modernity. You have a choice. You can choose to live in a community that still holds to older values. You can build a life, raise a family, and find allies who believe in the same things you do. You are a participant in a living debate.

In Norway, that debate feels finished. The ship has sailed, and anyone who questions its direction is treated as if they want to sink it; as if they are extremists or radicals. In Poland, there are still people arguing about the map. I would rather be in a society that is still arguing about its soul than in one that has already parted with it for comfort and safety. That, tangibly, is what has changed for me. I have exchanged comfortable consensus for a meaningful conflict.

There’s a million and one more things that I could have written about here, such as:

- The continual demonisation of investors and entrepreneurs by the ruling politicians, for reasons that still remain entirely unknown.

- How the government doubled down on highest taxation in the world despite having a budget surplus equal to 14% of its GDP in 2024. Again, for reasons unknown.

- How the railway network has shrunk since 1945.

However, this would be just rehashing the same tired point about economics and standards of living. Both of those topics are, in the grand scheme of things, fleeting and boring. This is why I choose to focus more on the intangible, incalculable things that people care about more: culture and tradition.

My intention is not to be polemic; to spit on Norway and its culture. Quite on the contrary, I am writing what I am writing because I am frustrated with how short Norwegians sell themselves. They can be so much more. If Norway at one point had the second-largest merchant marine in the world, why can’t they do it again? The spark is just not there anymore, yet it feels like I am the only one who takes this seriously. It’s not like I am trying to do backseat quarterbacking either: while I might not be in Norway anymore, I am most definitely going to work according to the Norwegian work ethic. I will advocate for labour unions if given the opportunity. If I see a business opportunity, I will seize it, as my host nation ancestors have done. For treating my cancer in 2019 through its public medical system, I have nothing but gratefulness for my host nation, so it is the least that I can do in return.

That gratitude is not platitude. It is a debt I intend to repay. This, then, is the multicultural exchange I spoke of at the beginning. It is not about abandoning one home for another, but about carrying the best of one’s heritage into the arms of another. I left Norway not because I hate it, but because I love what it once was, and what it could be again, too much to stand by and watch that spirit fade. Ultimately, my move to Poland was not an act of rejection, but an act of preservation – an attempt to keep that intrepid Norwegian spark alive, even if I had to carry the torch to another shore.

-

To be clear, I am not Roman Catholic. ↩︎