As always, before we get to meat of the matter, let’s first establish the terms. What is public school? In Europe, one most often does not think about school in terms of whether it is public or private, at least at the primary level. In Europe especially, public school is considered such an integral part of life that simply saying ‘school’ in the context of primary education is immediately understood. In places like Norway, private primary education is not even legal. This also means that public school is seldom examined critically.

But why is it important whether or not school is public or private? Why is that a necessary distinction? The distinction is in history, so let’s dive into it.

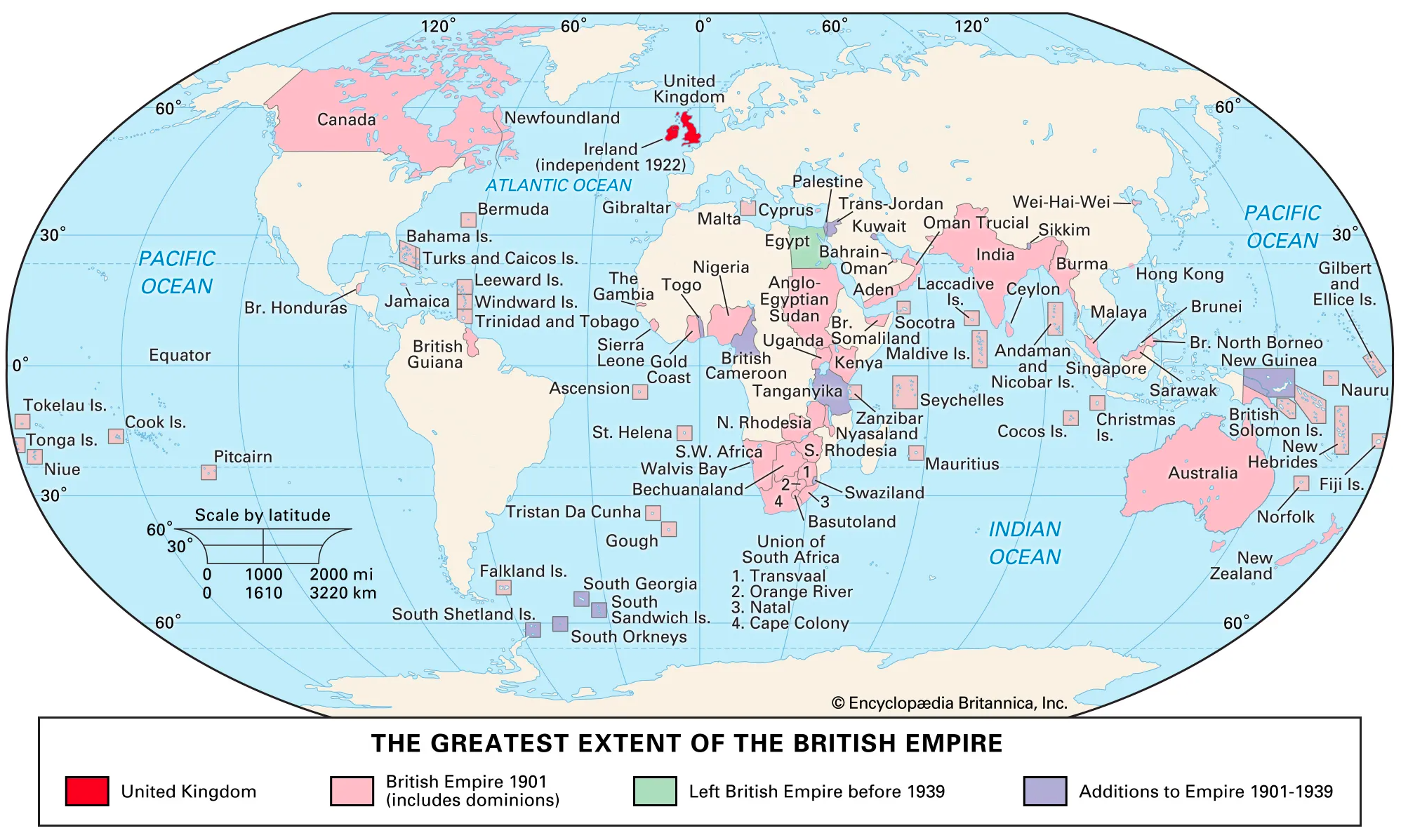

Public education did not become a serious proposition until the latter half of 19th century. That century was the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, which we feel the effects of to this day. The world hegemon at that time was the British Empire, sometimes also known as the empire upon which the sun never sets. If it was night in the British Isles, it was day in Singapore and Hong Kong. If it was night in New Zealand and Australia, it was day in British Caribbean. It was an enormous network of territories spanning a quarter of the globe.

British Empire at its greatest extent in 1901.

This raises an obvious question: how could the British Empire possibly maintain such an empire without the Internet or airplanes? The electrical telegraph did start rolling around by 1850, but it is of little help if your population is comprised largely of illiterates; small pool to draw bureaucrats from. According to Henry E. Cowper’s 1979 Ph.D. thesis, the answer is that they didn’t. The Italian Empire formed in 1869, the German Empire formed in 1871, and soon enough other countries started picking up this new hot thing called industrialisation. This meant fierce competition. The British Empire could no longer play it slow. In fact, they had some of the least educated citizenry in Europe. They had to pick up speed, but all of their strength laid in their dominions, which were all spread out throughout the globe. You could not control all of that with a few bureaucrats in Westminster. Rather, you needed bureaucrats in all the dominions, who are capable of independent calculation, assessment based on scholarly knowledge, and innate understanding of the protocols of trade and customs.

State-funded education, then, was the solution. The goal was not to foster creativity, critical thinking, or individual genius. It was to solve a massive human resources problem. The British Empire required a standardised, interchangeable class of administrators, clerks, and officers who could be relied upon to execute orders, maintain ledgers, and uphold the system without question, whether in London, Calcutta, or Hong Kong. It needed to mass-produce cogs for its vast imperial machine. The educational system that arose from this need was, therefore, designed with industrial efficiency in mind. Its primary aim was not the enlightenment of the individual, but the production of compliant and functional human components to serve the needs of the state and its sprawling commercial enterprises.

To achieve this industrial-scale production of bureaucrats, the system’s architects required a blueprint for mass conditioning. They found a perfect one in the most efficient and celebrated institution of their age: the factory. The internal logic of the public school is not the logic of the ancient Lyceum or the Renaissance studio; it is the logic of the assembly line. The ringing of bells to signal the start of a lesson, a break, or the end of the day was not an academic innovation. It was a factory innovation, designed to discipline a workforce and habituate them to the tyranny of the clock. Students were not grouped by intellectual curiosity or aptitude, but batched by their ‘manufacture date’, which was their age, and moved through a standardised process, from one subject station to the next, for a predetermined amount of time. The curriculum itself became a set of specifications for a uniform product: a citizen with a baseline of literacy and numeracy, ready to be slotted into a role. It was the perfect solution to maintain British supremacy over the continental wannabes.

This factory model, designed for efficiency, necessarily created an environment of coercion and rigidity. The physical layout of the classroom was optimised for surveillance and top-down instruction: rows of silent workers (students) facing a single foreman (the teacher). This was not the environment for exploration or discovery. The highest virtues were those of the factory floor or the military barracks: punctuality, obedience, and the silent completion of repetitive tasks. Critical thought, creativity, and dissent were not just unrewarded, they were liabilities to the operation. Which one? Of the grand empire. Not yours, stupid.

Of course, as with many things, this development was not exclusively negative. Rarely is this the case. Even the atomic bomb paved way for the best method of generating energy there is.

Indeed, the alternative to this new citizen factory was often the very real anguish of low-wage plebeian labour. Brutal labour. While Britain was engineering a system to produce compliant clerks, nations like Norway, contrary to any romantic notion of rustic Scandinavian life, actually made use of child labour to a greater extent than Sweden, Britain, or the United States. Before the state saw children as future bureaucrats, factory owners saw them as cheap labour, and nowhere was this more apparent than in the tobacco and matchstick industries. According to Statistics Norway research, a staggering 42 percent of the workforce in tobacco factories were children; in matchstick production, it was 35 percent. They were sent into these facilities to be exposed to toxins so potent they caused a condition known as ‘phossy jaw,’ where the white phosphorus would literally rot the bone from their faces.

Faced with a generation being physically disintegrated by industry, the state’s intervention with compulsory education looks less like an act of enlightenment and more like a pragmatic reclamation of a valuable resource. The research of Jakob Neumann Mohn, who chronicled this horror and would build the cornerstone of Statistics Norway, became the state’s blueprint. The explicit goal, in his own words, was “at beskytte Manden i Barnet”, or to protect the Man in the Child. Whether or not this was a sentimental plea is up for debate, but Mohn’s calculus was clear: a child maimed in a factory is a net loss to the state, incapable of becoming a productive worker or a competent soldier. He argued that child labour suppressed adult wages by creating a class of desperate competitors, and that it destroyed the workforce before it could even mature. The establishment of public schooling, therefore, was a strategic pivot. The state wrested control of children from the factory owners, pulling them from the chaotic brutality of the assembly line and placing them onto the structured, disciplined production line of the public school. It was a choice between two factories, but one of them didn’t actively dissolve your bones.

In the 20th century, the Norwegian Sami were subjected to a Norwegianisation policy with the goal of assimilation. The photo shows Sami children at a boarding school for migrant Sami children in Karasjok, 1950. The teaching was in Norwegian. I had to include something mean here, after all.

Now to the present. One would expect a lot to have changed over the course of 120-150 years. Usually, these sorts of developments undergo truly radical transformation over such long spans of time. The early Mercedes-Benz that Hitler rode is nothing like the latest 2025 C-Class. The electrical telegraph is now the Internet, a technology eclipsing its origins to such an extent that the remaining continuity is purely conceptual.

As we all know, however, the public school remains almost entirely unchanged from the early 20th century. The same organisation of classrooms remains. The bell still rings to signal the start and stop of playtime. With time, some countries even banned private alternatives to public primary education, as mentioned earlier.

In fact, I am going to argue that public schools have become worse in some significant ways since the times of Industrial Revolution. The chief of which is the formation of unisex schools. Contrary to what a fringe minority of deranged people would like us to believe, there are profound and inseparable differences between boys and girls. For instance, boys better learn visually, whereas girls through relationships. This is why comic books are popular with boys, whereas novels are popular with girls.

Girls mature at a faster rate than boys, and kind of just grow up to be women automatically, whereas a man is needed to turn a boy into another man. This is an especially pressing concern that, as far as I know, has never been addressed at any school in the west. I am sure there are lucky classrooms that have masculine teachers who are strong in character to guide both the boys and the girls towards not just educational success, but personal success. In my case, I have had nothing but melancholic teachers who clearly struggled with finding any joy in their work, perhaps even their lives as a whole. Most of them were women as well, clearly woefully untrained to deal with (often unique) problems that arise in boyhood.

What, then, is the practical result of this one-size-fits-all model, this deliberate ignorance of fundamental biology? The system, by default, ends up optimised for one sex at the expense of the other. The modern classroom prizes quiet compliance, orderly group discussion, and emotional introspection – a matrix of behaviours that aligns far more naturally with the developmental trajectory of girls. A boy’s innate drive for kinetics, competition, and tangible problem-solving is not seen as a different learning style, but as a behavioural problem. He is not channelled; he is pathologised. His inability to sit still for six hours is suddenly not a failure of the environment, but a defect in his brain chemistry, for which there is, conveniently, a medical diagnosis and a pill. The factory has simply been retooled to produce a different kind of compliant citizen, one neutered of the very masculine energy that built the empires in the first place.

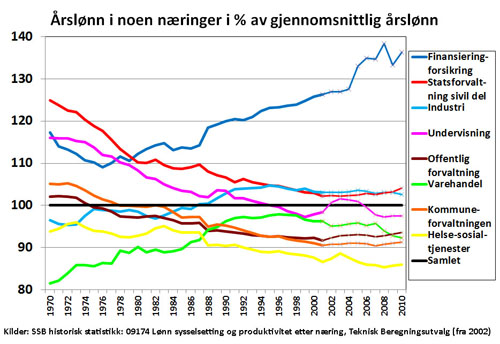

And who oversees this retooling? This system is overwhelmingly administered by women. This is not a failure of individual female teachers, many of whom are undoubtedly dedicated and competent, but a catastrophic failure of institutional design. A boy, who requires the firm example of a man to navigate the path to manhood, is instead left in a world of almost exclusively feminine authority during his most formative years. The few men who remain are often not the strong role models needed. They are the ones who haven’t quit despite truly lousy wages when compared to all other professions. From the boy’s perspective, school ceases to be a place of education and becomes an engine of weird social engineering, setting you on a path that you don’t understand. I didn’t understand why I had to read novels either, until only a few years ago. Turns out, I had to do it because it was never meant for me, it was for the girls.

Wages (in percentage of yearly average income) for certain sectors in Norway between 1970 and 2010. Pink line is education. It was 115% in 1970, in 2010 it was 97%. Source is Statistics Norway.

Of course, there are a few scholarly domains where sitting down and boring yourself with the details is the only way of learning an important topic. There are only a limited amount of ways of teaching mathematics in a way that imparts the needed mathematical skill.

Mathematics, chemistry, physics: these domains demand a foundation of brute-force memorisation and abstract logic. Few dispute this, but this is only a fraction of what a well-rounded school entails. What of history, of religion, of the arts? These are the realms of human drama, of epic struggle, of heroism and betrayal. Yet how are they presented? The thunder of legions and the ambition of emperors are reduced to a dry analysis of socioeconomic factors, or poetry nobody cares about. The great epics that were meant to forge a boy’s character are not even shown in class. Instead, we got tedious explorations of patriarchal power structures, or emotional inspection of a woman’s view on feminism, or something like that. These are all examples from my cloudy memory, mind you. Cloudy not because my memory from childhood is poor, but because these literary works really, really sucked.

This is where the model collapses into true psychological cruelty. When a boy is force-fed a curriculum that is not merely uninteresting but actively hostile to his masculine inclinations, he does exactly what a prisoner does: he rebels. Yes, we are finally getting to the title. He becomes disruptive, he disengages, he seeks distraction. And the system, in its profound lack of self-awareness, blames him for its own failure. The factory has thus perfected its design. It is no longer just a physical prison of bells and schedules; it has become a psychic prison, an environment engineered to alienate a boy from his own nature and convince him it is a pathology. The walls are no longer just brick and mortar; they are built from a curriculum that denies him heroes and a social structure that denies him masculine role models.

The dynamics of a prison and of the modern public school are eerily similar, but I will do you one better: prison has more positives over the public school. Let’s draw some parallels.

In a public school, you are there because you have to be there. Well, technically in places like Norway and most other countries, there is a duty to educate, not duty to send to school. However, given that most Norwegian parents do not have the personal resources for homeschooling, and private alternatives are banned, pretty much everyone gets sent to public school. With how fragmented, individualistic, and hyper-liberal modern western societies have become, you have kids in one place who come from radically divergent backgrounds, to the point where there is nothing fundamentally binding them together. Mass migration has made even ethnic basis a challenge. Decline in church life weakened family and community units. Basically, the entire place becomes a borderline mental asylum of idiosyncrasies, that the teachers often have few resources to handle, simply don’t care to handle, or maybe are even disallowed from intervening at all. God help you if your mother tongue is not Norwegian.

Meanwhile, in a prison, you actually have a lot in common with the other prisoners right out of the gate: you have sinned. Depending on the severity of your crime, there are no pretences that someone is below you or above you, that their family is different from yours, or that your mother tongue is not native. Of course, there is a large difference between most European prisons and what’s essentially a mass isolation chamber of El Salvador where most MS-13 gang members are destined to sit out the rest of their lives in complete silence, while being fed slop. In this essay, I am chiefly talking about Norwegian prison.

This fundamental difference in social cohesion leads to a second, more profound distinction: the presence of a clear, albeit brutal, code of conduct. The social landscape of a school is a jungle of unwritten rules, shifting alliances, and psychological warfare. Cliques form and dissolve, bullying is rampant but often subtle, and a student’s status can be destroyed by a rumour. It is a world of constant, low-grade anxiety governed by the whims of the immature. I speak from experience. A prison, by contrast, operates on a rigid and explicit hierarchy. The rules are harsh, and the consequences for breaking them are immediate and violent, but they are known. There is a brutal honesty to this system. Your place is understood, and navigating the environment, while dangerous, is a matter of understanding a clear (though unwritten) code. It is a world that demands situational awareness and respect for power; a harsh but straightforward lesson that is arguably more useful than navigating the chaotic emotional minefield of the schoolyard.

Furthermore, let’s consider the stated purpose versus the practical outcome. A school’s purpose is ’education,’ an abstract goal that for many boys translates into years of forced compliance with subjects they find meaningless. They leave with a diploma, perhaps, but few tangible skills that lead to self-sufficiency. A modern Norwegian prison, however, has a concrete and tangible purpose: rehabilitation. An inmate is often given the opportunity to learn a trade; to become a carpenter, a welder, or a mechanic. They can acquire practical, marketable skills in an environment that understands the value of tangible work. The school takes a boy, forces him to sit still, and lectures him on poetry. The prison takes a man, acknowledges his sins, but also need for purpose, and hands him a tool. One system prepares you for a life of abstract thought and bureaucratic compliance; the other can prepare you to actually build something, maybe even your own character. Absolutely nothing builds character like true repentance.

That is why, when someone told me that he knows several ex-convicts who preferred prison over school, I did not require further elaboration. I understood immediately why they said that. Now, when someone asks what the point of public schools is, if you can be taught most of the essentials at home, the usual answer I heard is, “For the social aspect.” Maybe people who respond this way have had a good time. I am not in a position to deny someone else’s anecdotal experience with my own testimony, but here are the things I was taught from social interaction at school:

- That you cannot trust anyone. Friendships are spontaneous, fleeting, subject to unsigned contract agreements.

- To hate other people. I have screamed at many students in bouts of unfiltered rage.

- Not to open yourself up too much to other people.

- That I am the problem, everyone else is correct. I was actually once berated by a teacher in high school for finding issue with music being played by a student in the middle of an ongoing lesson.

- To become addicted to pornography. If I was to be constantly anxious and on the verge of mental collapse, the natural outlet was pornography, readily accessible through the Internet.

Francis Bacon’s ‘Head VI.’ An accurate depiction of what the ‘social aspect’ of school feels like.

In my mind, this is the actual social curriculum. It is a fifteen-year masterclass in navigating a world without honour, a practicum in mistrust, and a seminar on the management of your own simmering resentment. When confronted with this reality, the assertion that ex-convicts might prefer the brutal honesty of a prison yard to the psychological warfare of the schoolyard ceases to be shocking. It becomes perfectly logical. A prison acknowledges the prisoner is broken and, in its best modern form, offers a some kind of path to rebuilding through repentance. The public school, in its current form, takes a healthy boy, convinces him that his own nature is a pathology, and offers him only compliance as a cure. One system breaks your body but can offer to rebuild your character; the other slowly grinds your character down and has the audacity to call it education.

Nearly every single insecurity that I have as a person is in some way tied to or originates from my years at public school. It was not until I was baptised at the Eastern Orthodox Church that I really started to understand the depth of my wounds (and evil). All of what I learned about socialisation had to be undone through over a decade of self-discovery, self-reflection, bitterness, anger, and confusion, before I really got an appreciation for the depth of the damage I received from school. I have mostly healed from all this damage, but I can still feel the subconscious fear when I walk by someone on the street if they stare at me for too long. If the 19th century public schooling system was a bureaucrat factory, the 21st century public school is a trauma factory.

To be clear, I am not implying that public school is the source of all evil in the world; that by eliminating it, we institute a utopia. In the modern world, there is an uncountable amount of ways to wound oneself, and still many other ways in which wounds are forced upon us. I am still quite grateful that I got the opportunity to learn how to read, write, do math, learn about some important history, and many other things that I still find use for in my life.

However, if there is one thing we should pray for every day, is that we do not witness more events like the one on 2nd April 2024 in Vantaa, Finland, where a 12-year-old stole his father’s weapon, took it to school, and murdered one of his peers. Clueless parents said, “We need to control guns better!” I said, “My God, it is a miracle our children are not terminated like this every single day.” I know, because this 12-year-old could have been me.