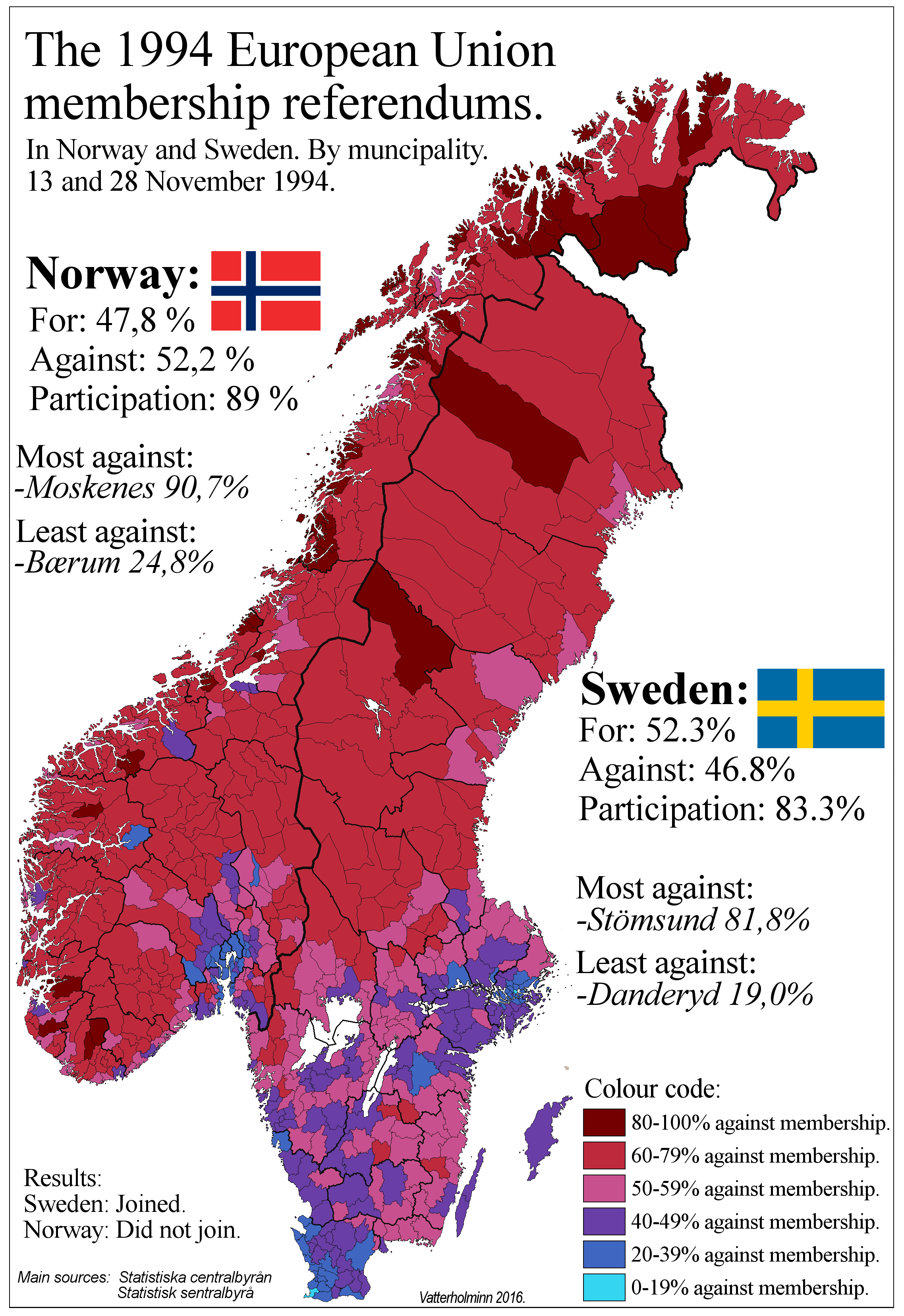

As far back as 1972, Norway had a referendum on whether or not to join the European Union (EU). For reference, this was so far back that the EU didn’t even exist yet. It was only the Economic European Community (EEC) back then. Narrowly, the population voted about 53% nay. There was another referendum, a lot more recently, in 1994. That time, it was even more narrow, with 52% voting nay. Sweden, which had referendum at around the same time, voted 53% yay instead, and became a member of the EU. This raises a perfectly obvious question: was the Norwegian public wise in these two landmark decisions? Clearly it is not a cut-and-dry issue, as all that decided the outcome was only about 100,000 people. If 100,000 more people were convinced that EU would be to Norway’s benefit – rather than to its detriment – Norway would have been an EU member in either 1972 or 1994. Let’s examine this more closely.

First of all, let’s identify what motivated the decisions in either referendum of the general public of Norway. According to Statistics Norway (Statistisk Sentralbyrå), the key fear of those voting nay in either referendum was loss of autonomy. Even back in 1972, when the EU was not a fully political union yet, 81% of those voting against EU membership cited this as a key factor in their decision. Even bigger portion still simply did not see any benefits, at 84%. Interestingly, even of those who voted positively for EU membership, 64% feared that EU membership would invite entry of foreign workers and foreign interests into Norway. In other words, even those who were receptive to EU membership were aware that some kind of compromises were pending, but saw that the advantages outweighed the perceived negatives.

Another factor for the outcome of both referendums was the rural-urban divide, with the rural Norway overwhelmingly voting against EU membership. In summary, key fear of the rural people was that piling Brussels on top of Oslo as an authority would overwhelm the ‘rural class’ of people, overriding their every decision or wish. As someone from Mandal who prefers rural life, I can resonate with this fear, even if I still think it was misplaced. In my experience, Brussels or not, the government is going to have its way with you.

Results of 1994 European Union referendums in Norway and Sweden. Statistics based on Statistics Norway.

These voter motivations more or less align with what I know from Norwegians, as someone who lived there my whole life. Throughout many conversations about Norway’s status in the world, I have repeatedly heard the following two words come up: independence (uavhengighet) and liberty (frihet). For example, why should Norway categorically ban imports of all potatoes forever? Because Norwegian farmers need to be free from foreign intervention and tyranny of cheap competition. In one particular case, I even heard the argument that Norwegians are uniquely the best people in the world when it comes to not wasting any food from grocery1, such as Coop or REMA 1000. According to that person, inviting competitors from abroad, such as LIDL or Aldi, would undermine this culture of saving food from waste. As a consequence, cultural independence and liberty of Norway would be infringed. Basically, the idea of ‘independence and liberty’ permeates the entire public conscience when it comes to foreign policy.

But that was the situation as seen by the general public of Norway. Let’s move onto the essential questions regarding the reality of Norway’s current situation as a non-EU member. What does Norway actually get out of not being in the EU?

It does not take much review to conclude that Norway is forced to play smart politics if it is to exist in Europe outside of the EU. The cornerstone of this strategy is the European Economic Area (EEA) agreement (EØS-avtalen), a deal that grants Norway access to the EU’s single market. This is, on the surface, the best of both worlds. Norway gets to trade freely with its largest partners, while remaining, officially, the master of its own house. But this arrangement has given rise to a uniquely Norwegian political problem, often described with the pejorative term fax democracy2. The term illustrates the reality of the situation: Norway receives laws from Brussels, as if by fax, and is obligated to implement them into its own legal code, all without (usually) having a single minister, representative, or even a junior aide at the table where those laws were drafted and voted upon.

This is not a trivial matter of conforming to a few trade standards. By some estimates, Norway has adopted roughly three-quarters of all EU legislation through the EEA agreement. This has led to the profound irony that in its quest for ‘independence,’ Norway has arguably surrendered more legislative power than it would have as a full member. As a member, it would have voting rights, the power of veto on key issues, and a seat in the European Parliament to shape the very laws it now passively accepts. On top of this, Norway pays hundreds of millions of euros to the EU each year for this market access; a fee without without representation. While the nay side can correctly claim victory in protecting key sectors like agriculture and fisheries from direct EU control, one must ask if the trade-off was worth it. Has Norway truly protected its independence and liberty, or has it simply exchanged a seat at the table for a stool in the hallway?

Of course, critics of this view have valid rebuttals. They will argue that the quarter of EU legislation Norway doesn’t adopt makes all the difference, particularly for cherished industries like fisheries and farming. They might also claim that Norway retains crucial ‘wiggle room’ in how it implements the laws it does accept. And they are not wrong. These exceptions and implementation details are significant. Yet, to focus on them is to miss the forest for the trees. The true cost of Norway’s arrangement isn’t found in the fine print of EEA directives, but in its silent shackles on the world stage.

What are those shackles? To understand, consider Hungary under Viktor Orbán. Now, one can vehemently disagree with Orbán’s politics – as many in Norway and across Europe do – but it is impossible to deny his effectiveness at using EU membership as a tool for his own national agenda. From a position of full membership, Orbán has repeatedly shaped, delayed, or outright blocked EU-wide decisions until his demands were met. He has used Hungary’s veto power as a powerful lever to extract concessions and advance his vision. Hungary does not even need powerful resources like oil and gas, as Orbán has a voice in the EU Council, and he uses it. For example:

- In January 2025, Orbán linked his support for extending EU sanctions on Russia to Ukraine reopening the transit pipeline for Russian gas.

- Despite Hungary holding the rotating EU Council presidency, Orbán traveled to Moscow in July 2024 to meet Vladimir Putin, without any EU mandate. EU leaders rebuked him for supposed appeasement and stressed he did not represent the bloc’s foreign policy position

- At a summer event in July 2025, Orbán warned he would torpedo the EU’s next seven-year budget unless Brussels unlocked billions in cohesion funds suspended over rule-of-law concerns. His ultimatum highlighted his willingness to use Hungary’s unanimity vote as leverage.

Viktor Orbán (left) meeting Vladimir Putin (right). From BBC News

Norway, in contrast, has no such lever. When the EU formulates a common foreign policy on everything from climate change to relations with Russia or China, Norway can only watch from the sidelines. It cannot play the spoiler, build a blocking coalition, or anything of the sort. As an economically ponderous petro-state, Norway definitely cannot leverage oil and gas. Wielding its oil and gas reserves as a political weapon, in the style of an embargo, is simply not in the nation’s political DNA. The Norwegian television thriller Occupied (Okkupert) vividly imagines the disastrous outcome if Norway were to pursue such a bellicose foreign policy. A nation of five million people, however wealthy, would be swiftly brought to its knees by giants like the EU, the US, or China.

Put another way, one could think back to the times Julius Caesar. Before he became emperor, he invaded Gaul and burnt its civilisation down to the ground. Despite being a fairly advanced civilisation, with fearsome warriors, the Gauls stood little chance against the much-better organised and powerful Roman Legions. Very little could have been done to prevent Gaul’s demise, but one thing that absolutely would have stopped all of Caesar’s ambitions would be simple: joining the Roman Republic.

Luckily, the EU is nowhere near as fearsome as Julius Caesar and his Legions, but the same principle applies in Norway’s situation. The point also isn’t to advocate for Norway to lead an aggressive foreign policy, where they threaten everyone with everything, including an oil embargo and the kitchen sink, if they don’t get their way. Current Norwegian foreign policy is more or less smart, even without EU in the picture. What is important to know, however, is that the current foreign policy isn’t implemented just because the Norwegian people want it: they have to implement it, lest they face seriously unpleasant consequences. Is this not by definition lack of independence and liberty?

For fifty years, this trade-off may have seemed acceptable. Norway’s immense oil wealth and the stability of the post-Cold War era created a comfortable buffer, making true political engagement feel optional. But the world is changing. With the USA’s suicidal foreign policy alienating European allies and the geopolitical ground shifting under everyone’s feet, the idea of standing alone is starting to look less like a proud choice and more like a dangerous vulnerability. Recent polls and analyses suggest that Norwegians are beginning to notice.

The core of the Norwegian dilemma has never been about paying fees to Brussels or the regulation of potatoes. It has always been about what self-determination is. The referendums of 1972 and 1994 answered the question for their time, choosing an ideal of liberty defined by separation; between rural and urban, and Oslo and Brussels. The question now is whether that definition still holds. In the turbulent decade to come, real independence may not be found in isolationism, but in the strength, influence, and security that comes from having a seat at the table. Only time will tell if a new generation of Norwegians will be forced to ask themselves the same question their parents and grandparents did, and whether they will arrive at a different answer.

-

As an aside, this is completely untrue. 450,000 tonnes of food is wasted every year across Norway. ↩︎

-

This article actually argues against the point I am making, but I thought I would include it to offer fair and nuanced representation of EU critics as it relates to Norway. ↩︎