By now, almost everyone in the industrialised world is aware of something known as ‘AI,’ or artificial intelligence for short. They might not use it, they might not have an idea of what it even is, but they are certain to be aware of the term. Among those who don’t know the particulars, they are largely indifferent. Those who are more technologically literate and curious about the technology, however, might have a strong opinion about it. People who don’t have a strong opinion about AI are just regular people. People who are convinced that AI is not just an industrial revolution, but something that will change the entire fabric society as we know it, we call the pro-AI cult. On the opposite side, we have people who say that AI will not do any of that, but rather cause the psychic, economic and creative death of the world as we know it; the anti-AI cult.

What is AI?

Before we get to any pro or anti cults, politics, legal issues, or whatever else concerning AI, let’s establish what AI even is. The term appeared seemingly out of nowhere, yet is now the backbone of every new startup in the Silicon Valley and elsewhere. The brand name ChatGPT is well on its way to replacing Google as stand-in for searching or extracting information from the Internet. Google-fu is getting replaced by prompt engineering, and so on. But what is it? What is the furore? Clearly, it cannot be actual intelligence, right?

In a very, very short and only somewhat reductive summary: AI is a word prediction algorithm on steroids.

However, that is not a very useful description, and might even seem very incorrect. After all, if AI is just a ‘word prediction algorithm on steroids,’ why are not just millions, or even billions, but trillions of US dollars getting poured into this technology across the globe? United Nations Trade and Development projects that market capital on AI technology might soar to near five trillion US dollars by 2033. With this in mind, it would be prudent to more exactly specify what AI is.

First of all, let’s establish the basics. The name ‘artificial intelligence’ is simply a marketing term that has no basis in the underlying technology. This is because, for a start, AI is not a single technology, but a wide swathe of technologies that use a common concept, but radically different implementations for different tasks: large language models (LLMs), image recognition models, diffusion text-to-image models, visual document retrieval models, and many, many more types. Given what was just said, it stands to reason that those terms are not very marketable to the average consumer, so the name ‘artificial intelligence’ was picked instead. For rich people, it was great. For researchers who want to do actual work and science free of marketing hype, it was an unmitigated disaster.

Secondly, the concept that makes up AI is not intelligence. In fancy terms, it’s about pattern recognition and generation at a scale that is impossible for the human brain to comprehend. Let’s take one of the most controversial (among a demographic of people I will get to later) types of AI: the generative adversarial network, or GAN. This is the technology that, for years prior to the explosion of ChatGPT, powered the ‘deepfake’ videos and hyper-realistic faces of people who don’t exist.

Understanding a GAN is surprisingly simple if you think of it not as a computer program, but as a game between two bots: an art forger and an art detective.

-

Generator (‘The Forger’): This bot’s only job is to create fakes. Imagine it starts by throwing random paint splatters on a canvas. It has no idea what a ‘Mona Lisa’ is. It just creates noise. Its goal is to create a painting that the detective will believe is a real, lost masterpiece.

-

Discriminator (‘The Detective’): This bot is the expert. It has been shown a massive library of every great masterpiece in history. Its only job is to look at a piece of art, either a real one from its library, or a fake from the forger, and declare ‘Real!’ or ‘Fake!’ It’s a seasoned art critic.

Click to expand.

Now, here’s where the magic happens. We pit them against each other in a relentless, high-speed battle. This battle is so intense and high-speed that it requires a lot of power from a lot of GPUs, which is why NVIDIA now has 4 trillion US dollars in market capital.

The Forger creates a terrible, noisy fake that doesn’t just not resemble Mona Lisa, but resembles nothing at all. The Detective looks at it for a nanosecond and says, “Fake! Not even close.” The system – that is, humans – tells the Forger, “That was bad. The Detective caught you instantly. Change your technique.”

Click to expand.

So the Forger adjusts its strategy slightly and produces a new fake. It’s still bad, but maybe the colors are a little more coherent. The Detective looks at it. “Fake. But I had to think about it for an extra millisecond.” The system gives that feedback to the Forger: “You’re getting warmer. Keep going in that direction.”

This process repeats millions, or even billions, of times. The Forger gets progressively better at creating convincing fakes, and in parallel, the Detective gets progressively better at spotting them. They are locked in an adversarial relationship, each one forcing the other to become smarter and more sophisticated.

What’s the endgame? The game stops when the Forger becomes so masterful that it can produce fakes that fool the expert Detective about 50% of the time. At that point, the Detective is essentially just guessing. The Forger’s creations are now indistinguishable from the real thing, at least in the eyes of the system. We can then take this masterful Forger, throw away the Detective, and use it to generate an infinite stream of novel, high-quality ‘art’.

Click to expand.

This isn’t intelligence in any meaningful sense, obviously. The Forger doesn’t feel inspiration, have any innate understanding of beauty, or anything of the sort. It is just a program that has been perfected through a computationally brutal game of competition. That is how a powerful algorithm can be produced, which allows previously impossible things.

Reality and the pro-AI cult

As we can see, conceptually GANs are fundamentally nothing different from any other computer program. The only difference from GANs compared to conventional computer programs is that GANs require an astonishing amount of data to learn from and computational power to run.

Microsoft datecentre located in Cheyenne, Wyoming, United States. It consumes many terawatt-hours every year, which is required to develop and run AI. More on this topic.

And as was mentioned, there are two cults that are obsessed with AI and vehemently opposed to everything related to it. The reason why this article will focus mainly on the anti-AI cult is because the pro-AI cult, sometimes also collectively called ’techbros,’ is more or less good at making itself look ridiculous already. Not much explanation is needed for why outsourcing thinking to AI is a very, very bad idea, or why substituting a would-be human girlfriend for AI is, again… a very, very bad idea.

Even for more practical tasks, discretion and expertise is required. For instance, a recent platform, called Tea, which was a dating platform designed exclusively for women – complete with government ID verification process – was trivially hacked. The issue? It is highly likely that the platform was ‘vibe-coded’ by highly inexperienced individuals, which led to the database being exposed to the public. All that was needed was finding the public URL to it – which was found – and the rest is history. The pseudo-programmers behind Tea ‘vibe-coded’ it, meaning that they used AI to essentially do all of the work for them. If they were more involved in the actual technical details of the project, they would see that the database program was screaming at them with obvious alerts, explaining that their database is publicly available at a given URL. In other words: AI is not a substitute for skill and paying attention.

Of course, there are some real serious benefits to AI technologies. The most notable example is that AI deployed at UK’s National Health Agency is better at detecting cancer from body scans than its oncologists are. An actual life-saving implementation! Indeed, there are many ways in which AI is generally beneficial. At the same time, the hype around AI is more than likely a bubble. So far, despite sky-high valuations that have propelled companies like NVIDIA past the GDP of most nations, clear and sustainable profits remain elusive for much of the industry. For all the talk of world-changing potential, the business models often boil down to burning through billions in venture capital to subsidise services in a race for market share: a strategy that reeks of the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s. Back then, ‘user growth’ and ‘disruption’ were prized over actual revenue, leading to an inevitable and spectacular crash. The current AI boom, fueled by what looks a lot like irrational exuberance, is showing similar cracks. This economic shakiness makes the pro-AI cult’s utopian promises seem even more unhinged, which is why I don’t really think they warrant a dedicated refutation.

Enter the anti-AI cult

Now we turn to the main subject: the anti-AI cult. If the pro-AI cult is defined by a naive, almost childlike faith in technology, the anti-AI cult is defined by a deep, conspiratorial paranoia. To them, AI is not a tool, however flawed. It is a parasitic, soul-sucking digital monster, birthed from theft and destined to bring about a creative and economic apocalypse. Their gospel is one of doom, their sermons filled with warnings of stolen art, mass unemployment, and the psychic death of human creativity.

Let’s be fair: some of these fears are rooted in legitimate anxieties. The question of how AI will impact jobs is a serious one, and the legal and ethical frameworks around data and copyright are struggling to keep pace with the technology. These are important conversations.

However, the central dogma of the anti-AI cult – the emotional engine that drives their movement – rests on a profound misunderstanding of the technology they so passionately despise. Their entire argument is built on a single, powerful, and fundamentally emotional premise that has no basis in legality or logic.

Stolen art!

The most common and emotionally charged accusation is that AI steals from artists. The narrative goes like this: AI companies scrape billions of images from the Internet, many of them copyrighted, and feed them into a model without the artists’ consent. Therefore, any image the AI generates is, according to them, a Frankenstein’s monster of stolen parts, an act of automated plagiarism on a planetary scale.

This is a common narrative. It is also wrong. The anti-AI argument treats the AI like a digital kleptomaniac, stuffing its hard drive with stolen JPEGs to stitch together later.

In order to understand why this is not the case, we have to define what plagiarism actually is. Plagiarism is governed by copyright laws, which I go into some detail in my other article. In short terms, plagiarism is creating something that is not creatively distinguishable from another artist’s work, or simply redistributing the work. This is wrong, which is why it is illegal in almost the entire world.

Does AI fulfil this legal definition of plagiarism? No. For context, an AI model is typically 1-100 GB of data, which is not nearly enough to contain the terabytes (TBs) or petabytes (PBs) of data that companies use to train said models. Obviously, an AI model cannot redistribute all the works of the world in that small amount of space. This simple fact of data compression proves that the AI is not a giant zip file of stolen images. Instead of storing copies, the model learns the statistical patterns and relationships between concepts.

To put it back in human terms, the AI is not a plagiarist; it is a student. When a human art student studies the works of Rembrandt, they are not storing a perfect photographic copy of The Night Watch in their brain. They are learning about chiaroscuro, composition, and how to render the texture of velvet and steel. When they later paint a portrait using those learned techniques, we don’t accuse them of stealing from Rembrandt. We call it being influenced by Rembrandt. The AI does the same, only it is a student that has studied the visual library of all of humanity. It learns the concept of cat from millions of pictures of cats, not by memorising any single one.

This brings us to the most crucial failure in the anti-AI cult’s logic: the inability to distinguish between a tool and the actions of a user.

Let’s consider a tool that artists have used for decades: Adobe Photoshop. With Photoshop, I can create a breathtaking, original digital painting from a blank canvas. I can also use it to take another artist’s work, clumsily erase their signature, and claim it as my own. I can use the clone stamp tool to remove elements, or the lasso tool to collage parts of copyrighted photographs into my work. Has Adobe created a plagiarism machine? Should we ban Photoshop because it can be used to infringe on copyright?

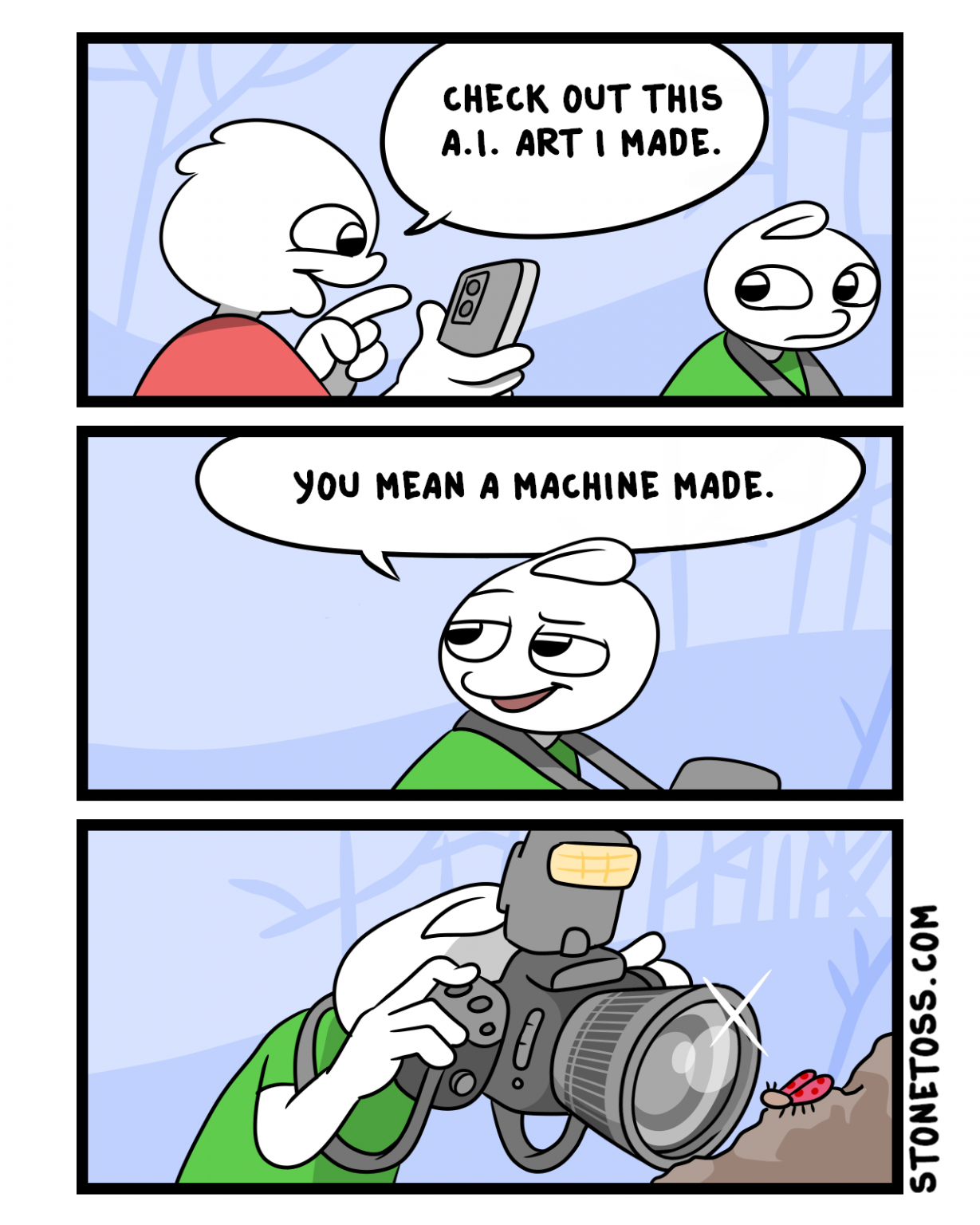

The question is absurd on its face. We understand that Photoshop is a tool. We hold the user accountable for their actions. If someone uses it to plagiarise, they are the plagiarist, not Adobe. If a big studio decides to plagiarise with Adobe Photoshop, we blame the studio, not Adobe. If a big company like Midjourney publishes a tool that accidentally allows you to recreate plagiarised content, we blame… all of AI, instead of telling Midjourney to fix their programming error? Alright.

AI is no different. It is simply a new paintbrush. A person can use this paintbrush to create something entirely novel and transformative. A different person, with malicious intent, could try to use this same paintbrush to replicate a specific artist’s style so closely that it borders on infringement. In that case, who is to blame? The paintbrush, or the person holding it?

The call to ban AI because of its potential for misuse is a fundamental category error. It is like demanding we ban cameras because they can be used to take pictures of copyrighted material, or banning the Internet because it can be used to distribute pirated files. It is nothing different from the outrageously stupid “You wouldn’t download a car” PSA of the early 2000s that played at the beginning of nearly every DVD film.

The anti-AI cult’s refusal to see this distinction is not based on logic or law, but on fear. Interestingly, given that AI art is often generic and mediocre, shouldn’t that fear be more indicative of the artist who is outraged over it, rather than AI? Food for thought.

The psychic death of creativity?

That final thought leads us to the second great dogma of the anti-AI cult: the fear that AI will not just steal jobs, but will destroy the very essence of human creativity. The argument is that if anyone can generate a ‘good enough’ image by typing a few words, the value of real skill, honed over years of practice, will evaporate. Art, they claim, will become a cheap, instantly gratifying commodity, and the human soul of the artist will be rendered obsolete.

This is, again, a compelling and deeply emotional fear. It is also, historically, a fear that has been proven wrong every single time a new creative technology has emerged.

When the camera was invented in the 19th century, painters panicked. The French artist Paul Delaroche, upon seeing an early photograph, famously declared, “From today, painting is dead!” Why would anyone spend weeks on a painted portrait when a machine could capture a perfect likeness in minutes?

But painting did not die. The camera did not kill it. By freeing painters from the burden of perfect realism, the camera forced them to ask a new question: what can painting do that a photograph can’t? The answer was an explosion of creativity that gave us impressionism, expressionism, surrealism, and many more. The camera ’took the job’ of pure representation, and in doing so, it pushed human artists into new, more expressive, and more abstract territories. It didn’t devalue human skill; it forced it to evolve.

AI is the new camera. It automates the technical rendering, the digital brushwork. It can produce a generic, technically proficient image on command. But it has no intent, no vision, no story to tell. It has no lived experience, no heartbreak, no joy. Anti-AI cultists often say this as some kind of checkmate, even to people who are obviously not in any way associated with the pro-AI cult. Everyone who isn’t part of either cult is keenly aware it is a tool or a novel amusement piece, and is treated as such.

Just like art schools of the 19th and 20th century, there’s a non-trivial amount of artists today who are gatekeeping elitists that refuse to adapt. The hills they will die on are often absurd to anybody who is not strongly opinionated about AI. In my opinion, the most eye-rolling AI outrage is about advertisement getting ‘invaded’ by AI. Ah, yes, won’t somebody think of the advertising companies? Won’t somebody pity the artists who are no longer forced to make graphics for obnoxious unsolicited content? “What we really need more of in our lives is human-crafted advertisement” is a hill that some anti-AI cultists are willing to die on. Doesn’t sound like defending creativity to me.

This defensive gatekeeping is the mark of an artist who fears their own mediocrity, not the sign of a true visionary. Can anyone seriously imagine a towering talent like Vangelis, a man who wrangled entire orchestras from a wall of synthesisers when that technology was in its infancy, being threatened by AI? The thought is laughable, isn’t it? A true master doesn’t fear a new instrument; they are hungry to master it. Vangelis would have either ignored AI as an amusing toy irrelevant to his vision, or he would have bent it to his will to create sounds and compositions we can’t even dream of. The outrage comes not from the giants, but from those who fear their own art sucks. In my experience, it often does.

“AI is bad for society”

You know what else is bad for society? Pornography and social media. I am not setting up a whataboutism here, like “Why don’t you care about this other, unrelated issue?” strawman, which is a lazy pseudo-intellectual rebuke. Rather, what I want to highlight is how societal attitude to the Internet is an all-around cataclysm that has ruined the lives of many people – particularly children – long before any of this silly AI outrage. Parents should not be letting their children use TikTok, or Facebook, or the Internet at all. The Internet is simply not good to use by the weak-minded.

If your goal of limiting or eliminating widespread use of AI is to protect society from ‘brain-rot,’ preventing children from abusing it or being abused by it, or anything of the sort, then you are simply barking up the wrong tree.

The moral panic surrounding AI seems like a convenient distraction. It allows people to fixate on a new sci-fi villain instead of confronting Moloch already living in our house: the attention economy and its devastating consequences on the human psyche. The psychological damage wrought by algorithmically-curated social media feeds on children is immense, with European Union Joint Research Centre pretty much saying that your brain actually will rot under its influence. The polarisation in society driven by engagement farming is also quite self-evident. The exploitation inherent in data collection – the list goes on. These are not future threats, they are the horrifying realities of our present. The anti-AI cult performs outrage over the potential for a robot to write a mediocre or plagiarised advertisement, while turning a blind eye to the very real, documented harm caused by the platforms on which that outrage is performed. They scroll through five hundred clips of playdough ASMR and pornographic content on TikTok, only to tweet outrage when one of the clips briefly contains an AI-generated image. It’s lunacy.

Conclusion: beyond the cults

This misplaced moral panic of the anti-AI cult is almost as ridiculous as the hysteria of violent video games or film piracy. By fixating on the tool instead of the culture, they divert energy and attention away from the real fight. Instead of demanding robust legal frameworks for data transparency from all tech companies, or banning decisively bad abuses of technology like pornography on the Internet, they demand a category of programs be banned; to prohibit GANs. Instead of advocating for educational reform to promote the critical digital literacy needed to navigate our toxic information landscape, they promote fear and outrage. They are trying to solve a 21st-century problem of information warfare with a 19th-century impulse to smash the machines. Thanks to that, the European Union has signed the AI Act, which essentially all it did was surrender any prospects of European economic supremacy to the US and China.

So we are left where we started: with two warring cults. On one side, the pro-AI cult, with its naive faith in technological salvation, blindly outsourcing its thinking and ending up with hacked dating apps and nonsensical business plans. On the other, the anti-AI cult, preaching a gospel of doom, demanding we unplug the future because they believe they are fighting the last war.

Both are wrong. Both substitute hysteria for reasoned debate.

The real path forward is to grow up. It’s to stop treating computer technology like it’s not just a binary sequence of zeroes and ones, and start seeing it for what it is: a tool. Very powerful, yet indifferent, and therefore a dangerous tool that demands skill, wisdom, and discipline from its users.

The anti-AI cult fears a future where creativity, or whatever else, is devalued by a flood of generic, machine-made content. But by refusing to engage, by choosing to scream from the digital sidelines instead of picking up the tool and pushing its boundaries, they are ironically helping to create the very future they fear. In those situations, it’s not a matter of winners versus losers. It’s a matter of those who scream at reality itself, expecting it to change, versus those who adapt to life and learn to deal with it. That’s just how it works.